The current representation of women in the GCSE history curriculum is minimal. It is arguable that a well-represented history education is essential for students to develop their wider understanding of gender roles in society. The GCSE history curriculum has been criticised multiple times for the male focused teachings it emphasises, and the kind of message it conveys to impressionable students.[1]

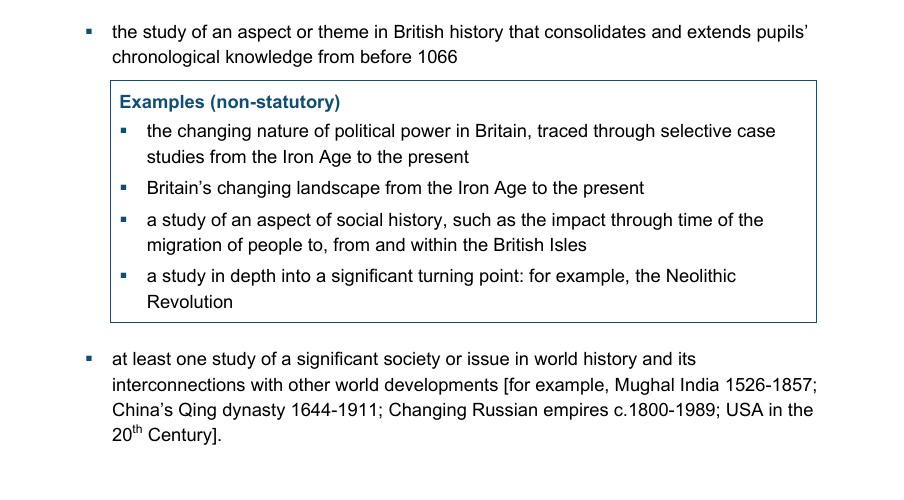

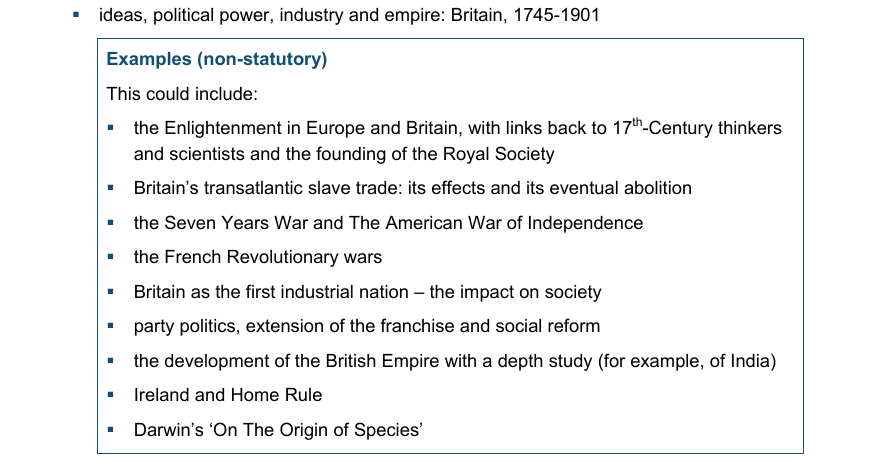

When many think of history lessons, most will likely start to think of Hitler and the second world war, or the Roman Empire. This is because these are two topics that the curriculum favours within British history. The common theme here is male dominance. The national curriculum for history states that students should be taught about the development of the Church and State in Medieval Britain, the development of Church and State in Britain 1509-1745, ideas, political power, industry and empire: Britain, 1745-1901, challenges for Britain, Europe and the wider world 1901 to the present day, local history, the study of an aspect or theme in British history that consolidates and extends pupils’ chronological knowledge from before 1066, and at least one study of a significant society or issue in world history and its interconnections with other world developments.[2]

The developments of Church, state and society in Britain 1509-1745 could include topics such as the English Reformation and Counter Reformation (Henry VIII to Mary I) and the Elizabethan religious settlement and conflict with Catholics (including Scotland, Spain, and Ireland). Despite not being the only topics that can be taught in reference to the developments of Church, state, and society in Britain 1509-1745, they are the only two that have some focus on women and their roles within the making of history. Similarly, challenges for Britain, Europe, and the wider world 1901 to the present day only really have women’s suffrage as a topic that shows women as an important aspect of history. It is extremely apparent to anyone reading the national curriculum that women do not have a primary focus in history education. Women are not perceived to be active agents in societal and historical changes, mainly having passive and minimalistic roles within the GCSE subject.[3]

Although there have been shifts in making the curriculum more inclusive towards the involvement of women, the achievements of male historical figures are still effectively overshadowing and minimising their success. With all of this in mind, it leaves many people questioning how are women being represented in the history curriculum?[4]

Through examination and the dissection of current GCSE history textbooks, it becomes apparent that women are being acknowledged for their place in history, yet they are being portrayed to be minor characters with minimal plot.[5] For example, when teaching students about the second World War, the focus points are often Adolf Hitler, Nazi Germany, or Winston Churchill. The roles and sacrifices women took during this time is often shown as a secondary contribution, providing Aryan children, or becoming nurses to help with casualties.[6]

The Suffragettes

The Suffragettes is one of the most used examples when it comes to women making history. Although the curriculum does include the study of The Suffragettes and their activism surrounding women’s voting rights, it is often taught as a stand-alone topic with minimal to no encouragement to be linking it to broader discussions.[7] This would be a good opportunity to make The Suffrage a focus discussion in the curriculum, and then link in other studies and events of gender roles standing up to political powers. After the analysation of subject material for the study of The Suffragettes, it becomes clear that the curriculum holds a strong focus on the violent and unlawful tactics they used rather than what they morally stood for; the constitutional rights for women.[8] Subsequently to this, it enables a false perspective on the activism that took place to be presented to students and does not open the topic into a wider discussion.

Women in WW2

The role of women in the second World War is another topic taught to students. This is a secondary topic within a much larger discussion that mainly focuses on men and the military, again showing women to be secondary. With the analysis of relevant textbooks, it is clear to see that some exam boards acknowledge the role women had in the war and the efforts they portrayed.[9] While the majority shows a favour to male military figures, such as Winston Churchill and Adolf Hitler.

In many history textbooks, the role of women can be sifted into two main categories; the involvement of women within the workforce, and the roles they held in the military. The outbreak of the second World War created and saw thousands of jobs to become available, with only women being available to take them.[10] Some of the jobs were in what would usually be male dominated fields, such as aviation and factory work.[11] The Women’s Land Army (WLA) became very popular due to their efforts in sustaining the food supply to the British. Women had also joined other organisations set up by women to help upkeep society while the war was ongoing.[12] The Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS), the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS), and the Women’s Auxiliary Airforce (WAAF) are some key examples.[13] Although these organisations were key to maintaining society and held key roles in the military, they are often taught to be supporting factors and not a key aspect of World War Two history.

A key aspect of the role of women in World War Two is their roles within intelligence and resistance.[14] Violette Szabo and Nancy Wake are two women that are rarely focused on. These two women worked as spies for the Special Operations Executive (SOE), and they worked relentlessly behind enemy lines.[15] The current GCSE History textbooks fail to explore the roles of these women in detail, creating them very little space in the classroom.

Although the physicality and the politics of World War Two was majorly male based, women equally gave up their freedoms to work with great effort for little to no consideration or acknowledgment. The way that World War Two is being presented to high school students often comes with the understanding that women had very minor roles and are just side stories in a much larger book, reinforcing the misconception that women primarily stayed at home during the war. It is essential for the roles women took on to be taught as a larger section in order to combat the views students develop around women in wartime, and women in general. It would be beneficial for the development of the understanding of gender roles, as well as allowing students to come to their own conclusions rather than having a forced narrative.

Other Case Studies

The representation of women in the curriculum is dependant on the time period being studied, and the events that took place. The GCSE curriculum does highlight the efforts of some female figures; however, they are often portrayed as side characters and unimportant compared to other male historical figures. Tudor Queens, such as Queen Elizabeth I and Queen Mary I, are two of the few women who are at the focus of their topic.[16] Queen Elizabeth I’s reign is taught to students with a focus on her court, the Spanish Armada, and the rivalry with her cousin Mary, Queen of Scots.[17] Overall, Elizabeth is presented to be a strong and powerful anomaly in a male dominated society. The curriculum does not focus on her power as a woman in politics, and it does not open the discussion wider to compare and contrast other ruling women and female political influence.[18] Because of this, it reinforces the message that strong women in power is rare, and often unheard of. The impact of Queen Elizabeth’s political power is often reduced to her being a female, and a virgin, and does not take the opportunity to create a wider discussion within the classroom.

Rosa Parks is another female that is centred within a topic. The Civil Rights Movement and Parks’ Montgomery Buss Boycott is a pivotal part of American History and the fight for race equality and civil rights.[19] Although remembered as the girl who refused to give up her seat, Rosa Parks is much more, and did so much more. Before her bus boycott in Alabama 1955, Parks’ was an active member of the Civil Rights organisation the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP).[20] However, due to the focus on other Black male activists, such as Malcome X and Martin Luther King Jr, the teaching of Rosa Parks is limited to her Montgomery Bus Boycott.[21] The failure to recognise Parks as a lifelong activist significantly downplays her role in fighting segregation. The curriculum also erases the efforts of other female activists, such as Ella Baker, Claudette Colvin, and Jo Ann Robinson. Rosa Parks has been known as the woman who refused to give up her seat, but she is far more calculated, strategic, and determined than the curriculum allows students to understand.[22]

How women’s roles are framed

The GCSE History curriculum and corresponding textbooks often present women to be minor aspects of history and minimise their contributions while reinforcing gender inequality.[23] Although women are present in some topics, such as women in WW2, the Suffragettes, and Queen Elizabeth I, their contributions are not fully explored.[24] They are often depicted as supporting roles, and not as agents of change, with a wider discussion not being actively encouraged.

It is evident when looking at the interpretation of women in topics such as the second World War and the Civil Rights Movement, that women are supporting, secondary ‘characters’, while men are at the forefront of all wider discussions.[25] Churchill, Hitler, and Martin Luther King Jr are dominating the curriculum and creating established opinions, whereas the limited female representation in history education is feeding gender bias, stereotypes, and inequality.[26]

The use of language in the current History textbooks also further enables the poor representation of women. When descripting women, their emotions and personalities are often commented on, whereas the language used to describe men is all about their leadership and power.[27] The use of language in textbooks is highly influential for the development and shaping of student opinions and views. The use of derogatory language degrades women and implies that their contributions in history are insignificant compared to the male contributions.[28]

Women are also rarely used within larger thematic discussions or debates within the classrooms. Due to their minimal representation in the curriculum, the topics do not allow for a discussion to led based off of their political and intellectual developments. Unlike how Hitler and Churchill have many large discussions for war history and political intelligence, women are often reduced to social history only, as seen with the topic on Elizabeth I. Elizabeth’s power within the court is looked into, as well as the Spanish Armada, yet the failure to link her female power and political intelligence to other examples is a disservice to women in history and their efforts.

The minimal representation and lack of thematic discussions does not allow students to develop a fair understanding, and further enables the prejudice towards women to continue.[29] The limited discussion opportunities and lack of background history creates a distorted understanding on the topics being taught, showing women to sit on the side-lines and have minimal contributions when they do.

In order to see a more inclusive and represented history, women’s history should be linked to wider discussions, such as political and economic. This will allow for students to understand their ability, leadership, and agency within a wider historical context, and create a new perspective where women are not seen as side-line characters and supporters of men.

[1] Debbie Epstein et al., Failing Boys?: Issues in Gender and Achievement, Vlereader.com (Open University Press, 1998), https://r2.vlereader.com/Reader?ean=9780335231508

[2] Department for Education, “National Curriculum in England: History Programmes of Study,” GOV.UK, September 11, 2013, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-curriculum-in-england-history-programmes-of-study/national-curriculum-in-england-history-programmes-of-study

[3] Department for Education, “National Curriculum in England: History Programmes of Study,” GOV.UK, September 11, 2013

[4] Sebastian Barsch, “Historical Thinking, Historical Knowledge and Ideas about the Future,” Journal of Curriculum Studies, April 22, 2025, 1–22, https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2025.2496463.

[5] Audrey Osler, “Still Hidden from History? The Representation of Women in Recently Published History Textbooks,” Oxford Review of Education 20, no. 2 (1994): 219–35, https://doi.org/10.2307/1050624.

[6] Audrey Osler, “Still Hidden from History? The Representation of Women in Recently Published History Textbooks,” Oxford Review of Education 20, no. 2 (1994): 219–35,

[7] Department for Education, “The National Curriculum in England Key Stages 3 and 4 Framework Document,” GOV.UK, December 2014, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5da7291840f0b6598f806433/Secondary_national_curriculum_corrected_PDF.pdf.

[8] Maria DiCenzo, “Justifying Their Modern Sisters: History Writing and the British Suffrage Movement,” Victorian Review 31, no. 1 (2005): 40–61, https://doi.org/10.2307/27793564

[9] Corbin Elizabeth Schrader and Christine Min Wotipka, “History Transformed? Gender in World War II Narratives in U.S. History Textbooks, 19562007,” Feminist Formations 23, no. 3 (2011): 68–88, https://doi.org/10.2307/41301673.

[10] Claudia Goldin, “The Role of World War II in the Rise of Women’s Work,” Ssrn.com, December 1989, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=226717.

[11] Emily Yellin, “Our Mothers’ War American Women at Home and at the Front during World War II,” Google.co.uk, 2004, https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Our_Mothers_War/xxCe8vXq30YC?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=women+in+world+war+two&pg=PR9&printsec=frontcover.

[12] Cecilia Gowdy-Wygant , “Cultivating Victory the Women’s Land Army and the Victory Garden Movement,” Google.co.uk, 2013, https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Cultivating_Victory/PXLgDwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

[13] D’Ann Campbell, “Women in Uniform: The World War II Experiment,” Military Affairs 51, no. 3 (July 1987): 137, https://doi.org/10.2307/1987516.

[14] Sarah-Louise Miller , “The Women behind the Few the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force and British Intelligence during the Second World War,” Google.co.uk, 2023, https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/The_Women_Behind_the_Few/n_qZEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0.

[15] “Secret Agents of World War II | Violette Szabo Museum,” Violette-szabo-museum.co.uk, 2024, https://www.violette-szabo-museum.co.uk/agents.html.

[16] Department for Education, “National Curriculum in England: History Programmes of Study,” GOV.UK, September 11, 2013

[17] Mosslands High School, “GCSE History Elizabethan Age, 1558-1603 Revision Guide,” n.d., https://www.mosslands.co.uk/attachments/download.asp?file=1619&type=pdf.

[18] BBC Bitesize, “The Elizabethan Era, 1580-1603 – the Elizabethans Overview – OCR B – GCSE History Revision – OCR B,” BBC Bitesize, 2025, https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/zwmr7hv/revision/1.

[19] NAACP, “Rosa Parks | NAACP,” naacp.org (NAACP, 2022), https://naacp.org/find-resources/history-explained/civil-rights-leaders/rosa-parks.

[20] NAACP, “Rosa Parks | NAACP,” naacp.org (NAACP, 2022).

[21] BBC Bitesize, “Malcolm X, the Nation of Islam and Black Nationalism – Civil Rights 1941-1970 – Eduqas – GCSE History Revision – Eduqas,” BBC Bitesize, 2025, https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/zkrgg7h/revision/6.

[22] National Museum of African American History and Culture, “Women in the Modern Civil Rights Movement,” n.d., https://nmaahc.si.edu/sites/default/files/images/black_women_civil_rights_movement_1.pdf.

[23] Sheila Rowbotham , “ Hidden from History 300 Years of Women’s Oppression and the Fight Agai,” Google.co.uk, 2019, https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Hidden_From_History/xnXJUO6IG80C?hl=en&gbpv=0.

[24] Department for Education, “National Curriculum in England: History Programmes of Study,” GOV.UK, September 11, 2013, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-curriculum-in-england-history-programmes-of-study/national-curriculum-in-england-history-programmes-of-study.

[25] Danielle Handley , “‘Why Is My Curriculum so Male?’ Assessing and Redressing the Gender Imbalance in the History Syllabus,” Academia.edu, 2018, file:///C:/Users/phoeb/Downloads/Why_is_my_curriculum_so_male_Assessing.pdf.

[26] Corina Balaban, “Listening-To-Student-And-Teacher-Voices,” Aqa.org.uk, 2021, https://www.aqa.org.uk/blog/listening-to-student-and-teacher-voices.

[27] Hassan Kazmi, Shahida Khalique, and Sarah Ali, “GENDER REPRESENTATION and STEREOTYPING in EFL TEXTBOOKS: A CRITICAL DISCOURSE ANALYSIS,” Pakistan Journal of Society, Education and Language (PJSEL) 9, no. 2 (2023): 304–18, https://pjsel.jehanf.com/index.php/journal/article/view/1172.

[28] Saeed Esmaeili and Ali Arabmofrad, “A Critical Discourse Analysis of Family and Friends Textbooks: Representation of Genderism,” International Journal of Applied Linguistics and English Literature 4, no. 4 (2015): 55–61, https://journals.aiac.org.au/index.php/IJALEL/article/view/1434/1392.

[29] Royal Historical Society, “Reading, Gender and Identity in Seventeenth-Century England | Historical Transactions,” Royalhistsoc.org, 2025, https://blog.royalhistsoc.org/2025/04/10/reading-gender-and-identity-in-seventeenth-century-england/.